Since the establishment of the Dubai Quality Award in 1994, what began as a government initiative has grown into one of the most influential catalysts for a culture of excellence in Dubai’s private sector. As the first program of its kind in the region, the award sparked an unprecedented leap in service standards and adherence to quality benchmarks across Dubai and beyond. Over the past three decades, more than 2,000 organizations from various industries have undergone the award’s evaluations, yielding tangible improvements in operational efficiency, customer satisfaction, and sustainable performance. Local economic reports indicate that companies honored with the award recorded 15% to 25% higher productivity growth than their industry averages in the years following their recognition.

This transformation in the business environment aligns with Dubai’s drive to build a competitive economy on the back of outstanding institutional performance. The award’s rigorous assessment mechanism, rooted in the European EFQM excellence model, compelled many companies to adopt data-driven management, effective governance practices, and continuous innovation. In doing so, it significantly raised the maturity of the emirate’s business ecosystem.

Sheikh Mohammad bin Rashid Al Maktoum, who at the time served as head of Dubai’s Department of Economic Development (and today is the emirate’s ruler and the UAE’s Prime Minister), played a pivotal role in shaping the award from the outset. He viewed it as “a platform for creating excellence, not just for honoring the excellent,” as he said in one speech. The award’s launch coincided with broader efforts to upgrade Dubai’s economic infrastructure and instill a new governing philosophy that treated quality as key to sustainable growth, a novel approach in the region that has influenced Dubai’s development over the last thirty years. By the same token, the footprint of quality expanded dramatically among smaller businesses: according to Dubai’s Department of Economy and Tourism, the share of small and medium-sized enterprises meeting the award’s quality criteria jumped from just 7% in 2005 to over 38% by 2022.

Beginnings

In 1993, as Mohammed Al Gergawi “then Director of Finance and Administration at Dubai’s Economic Development Department” attended an internal training program at Mashreq Bank (then known as Bank of Oman), a brief booklet titled “Total Quality Management” caught his eye. The text was short but introduced powerful ideas, including a maxim by American quality guru W. Edwards Deming: “Quality is everyone’s responsibility, and it cannot be delegated to a single department.” These principles sparked an early awareness in Al Gergawi who would soon be tasked by Sheikh Mohammed with launching Dubai’s quality program of the importance of building an institutional environment grounded in systematic standards. Quality, he realized, had to go beyond individual effort and become part of an organization’s collective DNA, cementing the foundations of effective teamwork.

When Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid issued directives to establish a government system centered on excellence and quality, Al Gergawi responded with a comprehensive proposal that drew on global models like EFQM and America’s Malcolm Baldrige criteria. With that proposal approved, the contours of what would become the Dubai Quality Award began to take shape.

Gergawi later recounted how those training sessions at the bank became the seed of the Dubai Quality Award. “We wanted to create something for Dubai in the field of quality,” he recalled in an interview. “So we submitted a proposal to Sheikh Mohammed… and he approved it.” That approval, he noted, was no routine sign-off it was a strategic move reflecting a broader vision to shift Dubai from being merely a trading hub into a city that also mastered the quality of performance within its institutions.

At the time, Gergawi’s team had little more than “two courses on quality and some enthusiasm,” as he tells it. They set out to find a reference framework that could translate these ideas into measurable indicators. Their search led to FedEx, the U.S. logistics company that in 1990 became the first service business to win the national Malcolm Baldrige Quality Award. FedEx’s success was living proof that quality wasn’t just the domain of manufacturing as was then assumed but a principle that could apply to any sector, from private services to government. The Dubai team obtained FedEx’s detailed evaluation documents and studied them alongside the EFQM framework from Europe, which Dubai would officially adopt later.

By 1994, the Dubai Quality Award was launched, heralding a new approach that linked operational efficiency with customer satisfaction. This approach recognized that quality begins with understanding consumer needs and meeting them at the lowest possible cost and that the greatest expense any organization bears is the cost of errors. Cutting mistakes and redesigning processes became central tenets of the quality philosophy, which was introduced not as a marketing slogan but as a management system to boost performance and make excellence a daily practice.

Raising the Bar: The 1994 Launch

At the award’s inauguration in 1994, Sheikh Mohammed tasked the Department of Economic Development with deploying it as a tool for measuring institutional performance rather than just handing out trophies. The award criteria drew on a blend of the U.S. Malcolm Baldrige standards, which emphasize strategic leadership, and the European EFQM model, which links efficiency to how resources are used to achieve results. The result was a local framework with ten criteria divided between “enablers” (such as leadership, strategy and resources) and “results” (covering outcomes for customers, employees and society).

Once it got underway, the Dubai Quality Award quickly evolved from a scheme to honor top performers into a benchmark that ranked organizations by actual performance rather than reputation. Quality became a non-negotiable baseline. Companies that once treated quality as a buzzword for marketing suddenly faced new pressures Dubai began, for instance, linking business licensing and government partnership opportunities to annual quality evaluation results. Policymakers came to see the quality standard as a regulatory tool akin to taxes in state-building, imposing a shared obligation that bolsters trust and transparency. In this way, the award turned into a mechanism of governance, tying economic performance to social responsibility.

Quality as a Social Contract

Behind the award lies a philosophy broader than the technical calibration of production standards. It is an attempt to reshape the social contract itself so that the right to quality service becomes part of one’s citizenship and a precondition for an institution’s legitimacy. In the model Dubai adopted, the time a customer spends completing a transaction is redefined as a moral currency, as valuable as money. Respecting people’s time equates to respecting their dignity, and the transparency of performance metrics becomes a tool to renew trust between the governing and the governed. If modern authority, as John Locke put it, rests on the “tacit consent” of the governed, then publishing quality results openly turns that consent into a measurable number making excellence a social duty before it is an economic advantage.

This logic helped forge something akin to an “organizational oath of ethics,” by which companies pledge to society that quality is a condition for survival, not just a mark of distinction. Contemporary management literature on the EFQM model reinforces this idea: a company’s responsibility to its stakeholders is built into the evaluation criteria, aligning performance with conduct. One study of firms that won the award found that participating in its process helped entrench a culture of legitimacy based on competence within those organizations a channel, researchers noted, for boosting public confidence in the private sector’s social role.

Herein lies the award’s deeper philosophy: just as modern constitutions compel citizens to pay taxes and protect public infrastructure, Dubai’s quality model demands that every entity governmental or private pay another kind of tax, namely a commitment to standards that enable society to hold it accountable. Quality, in this sense, is more than a certificate to hang on the wall; it’s an implicit contract that redistributes symbolic power in the economy toward those who excel in service delivery, not merely those who control capital.

A Legacy in Numbers

Nearly thirty years on, the Dubai Quality Award’s impact can be read in hard numbers that carry an ethical and economic weight of their own. By 2018, some 169 companies across more than ten sectors from finance to education to tourism had earned formal recognition through the award. In the 29th award cycle, in March 2023, Dubai’s Economy and Tourism department honored 46 entities (20 winning in the main award categories and 26 receiving customer service excellence awards) in a ceremony that drew over a thousand participants on a single virtual platform.

The real significance, however, lies in the “moral marketplace” the award helped create. Across all cycles to date, more than 23,000 applications have been submitted for the Dubai Quality Award, producing roughly 700 winners. Their performance was scrutinized by a pool of over 3,000 assessors and some 500 mystery shoppers who fanned out to experience and measure service quality firsthand. The accumulation of data from 29 cycles has built a collective statistical memory that evaluates entire sectors through neutral eyes, allowing regulators to tweak incentive schemes or even penalties using a transparent yardstick.

From Kaizen to a Moral Economy

Dubai’s model drew inspiration from Japan’s kaizen philosophy of continuous improvement through incremental steps a methodical pursuit of “perfection.” Yet the architects of the Dubai Quality Award reframed kaizen within a cultural context that elevates Arab hospitality as an ethical commitment to others. In Arab tradition, a cup of coffee is offered not merely to satisfy a physical need but to affirm a guest’s dignity and show respect. In that spirit, continuous improvement became an extension of hospitality: every administrative procedure or business service is like another cup of coffee that must be kept consistently hot, hot in terms of timely delivery, and hot in terms of accuracy.

Against this backdrop, the notion of a “moral economy” took hold. A company’s market value came to be gauged not only by its earnings, but by how much it contributes to raising the public’s expectations of good service. That intangible factor builds what might be called “empathy capital,” which increases customer loyalty and protects a company in times of crisis more effectively than any ad campaign or price promotion.

Impact on Business and Government

Quantifying the award’s impact reveals a dual effect on human capital and market value. On the internal side, an academic study found that Emirati companies which earned the award markedly improved their human-resource development practices and lowered operational risks helping sustain cash flows and narrow compliance gaps. Consider Dubai Electricity and Water Authority (DEWA) and its subsidiary Empower: in 2024, DEWA’s digital services platform saw a 12% jump in electronic transactions over the previous year. That growth translated directly into greater staff productivity, since employees processed more services in the same amount of time. In this way, the Quality Award brought not just symbolic prestige but a concrete boost to organizational efficiency.

From the market perspective, data from Emirates Central Cooling Systems Corporation (Empower) a district cooling provider listed on the Dubai Financial Market showed revenues rose about 7% year-on-year after it adopted excellence systems based on the award’s criteria. It’s a real-world example of how a reputation for quality can draw in new capital and widen profit margins without raising prices. This outcome mirrors a classic study in the journal Management Science, which found that companies experience nearly a 1% abnormal stock return on the day a quality award is announced, with even larger cumulative gains over time. In other words, the markets tend to interpret a quality accolade as a positive financial signal.

Meanwhile, the award’s imprint on the public sector is evident in a 2025 study of an agile overhaul in DEWA’s power substation projects. By applying Agile project methods, delivery times were cut by 30%, saving roughly 1.8 million dirhams (about $490,000) per station evidence that quality is not just about box-checking, but a means to reduce capital risks and speed up social returns on investment. In economic terms, the award has become a mechanism to boost profit margins and lower risks at once; in administrative terms, it’s a catalyst spurring government agencies to re-engineer processes with real-time data and accountable performance metrics.

Quality and Political Legitimacy

Across modern city-state models, service quality has emerged as a tool for cultivating political legitimacy albeit in different ways. In Singapore, the government crafted a clear contract with its citizens: the public grants obedience to a strong state in return for exceptionally efficient services. Quality, in this model, underpins a “legitimacy of compliance,” where a somewhat authoritarian bargain is justified by world-class schools, transport and digital governance, all coordinated by a Civil Service Bureau under the Ministry of Finance through annual performance contracts and Balanced Scorecard targets.

Dubai, by contrast, flipped the equation. The emirate did not invoke quality to validate an existing central authority; it used quality to create a new basis of authority, one measured and continually renewed by performance. The government shifted from acting as a paternalistic “benevolent provider” that doles out resources as favors, to serving as a “guarantor of standards” that sets red lines for performance and vigilantly guards the customer experience through live dashboards and public KPIs.

This shift changed the relationship between citizen and institution. Instead of petitioning gratefully for services handed down as favors, the customer now holds a measurable, contractual right to decent service and can hold a lagging agency to account based on a norm of performance rather than a norm of loyalty. In this context, the legitimacy of Dubai’s government is rooted in the efficiency of its procedures and the transparency of its outcomes, not in any open-ended paternalistic promise. The government is effectively held to account like a Fortune 500 company, judged on metrics such as wait times at service centers, customer satisfaction rates, and the percentage of projects delivered on schedule. Conversely, public agencies that exceed their targets earn extra funding or upgraded institutional ratings. This dynamic deepens the transition from an old administrative rentier system to an economy of standards, where performance is the true political capital.

Toward a Real-Time Quality Regime

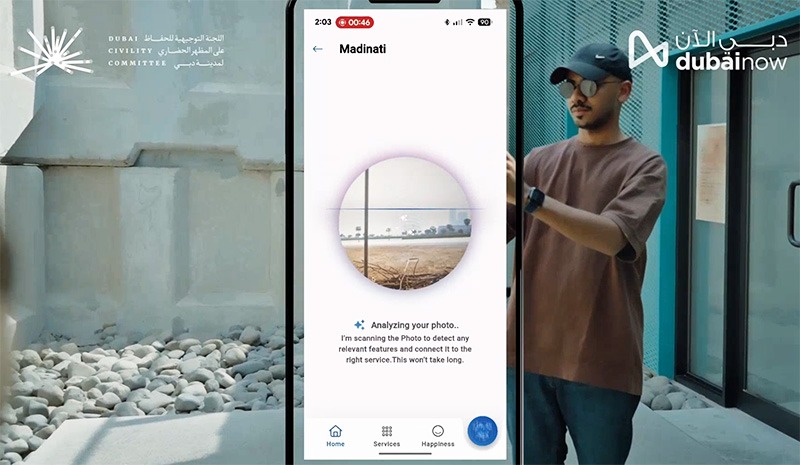

Dubai’s authorities are now upgrading the Quality Award model from an annual event into a real-time, tech-driven platform. The Department of Economy and Tourism has teamed up with technology partners to build advanced analytics that can predict service quality on the fly. One new system aggregates tourism data from 20 major global markets and reacts instantly to customer-experience indicators actual wait times, the percentage of unresolved complaints, social media sentiment and more. These inputs feed into a continuous quality rating displayed on internal dashboards and even injected into the Dubai Now app, which offers over 280 government and private services from 44 entities. In effect, the user is becoming a partner in measuring performance rather than a passive recipient of services.

Philosophically, this moves the notion of quality from a once-a-year celebration to an always-on governance tool. An agency’s legitimacy is no longer checked at twelve-month intervals; it is weighed around the clock by a digital twin of the UAE’s star-rating system for public services (which grades agencies on a 2-to-7-star scale). Injecting immediacy into the process turns a director general from an occasional decision-maker into a constant monitor, correcting course like an autopilot and continually recalibrating incentives. Soon, partnership contracts and government funding will be tied to an organization’s live star rating, not just last year’s scorecard.

Operationally, integrating algorithms with leadership dashboards means every digital customer interaction becomes a data point recorded on an immutable blockchain ledger. In effect, a “transparency tax” is paid up front, giving institutions early warning before their public image deteriorates. In this new paradigm, the customer’s right to good service, the investor’s risk calculations, and the executive’s accountability all converge in one real-time interface that updates in seconds. It heralds a quality regime that lives as much on officials’ screens as it does on citizens’ smartphones.

When Standards Become Solutions

Each year, government agencies and businesses vie for Dubai’s quality awards, and the winning projects show how abstract standards translate into concrete benefits for society. In Dubai, for example, the police department earned the “Smart Government & Digital Transformation” award for its “Digital Twin and Crime Scene Reconstruction” initiative, which creates 3D digital replicas of crime scenes so forensic teams can examine incidents from multiple angles with greater precision. Meanwhile, Dubai’s Roads and Transport Authority won the “Technologies” award for its Enterprise Command and Control Center (EC3), a unified 24/7 operations hub that merges data from all modes of transport to improve traffic management and logistics.

In Abu Dhabi, the Civil Defense Authority received a Smart Government award for its “Smart Ambulance Systems” project. The initiative equips ambulances with tablet devices that transmit patients’ vital data to hospitals in real time and activate algorithms to prioritize emergency vehicle routes reducing response times and improving survival rates.

In the smaller emirate of Ajman, the municipality won accolades for two projects. The first was a “Green Concrete” initiative that used concrete mixes containing up to 90% recycled material, cutting carbon emissions by roughly 80% compared to standard concrete and earning an award for environmental innovation. The second was an e-government platform called “Tasdeeq” that digitizes the attestation of rental contracts with zero paperwork, simplifying procedures and bolstering trust in the real estate market. Ajman’s police force was also recognized with a “Zero Bureaucracy” award for “Honoring the Departed,” a program that consolidates the issuance of death certificates, the waiving of outstanding fines, and the coordination of funeral arrangements into one streamlined process to ease the burden on bereaved families.

Collectively, these initiatives show how lofty quality benchmarks can yield practical solutions that simplify lives and reduce environmental impact. They reflect a widespread commitment across federal ministries and local departments alike to continuous improvement and innovation in public service.

Three decades after a journey that began with a slim booklet in a Dubai bank, the Dubai Quality Award has become a strategic compass recalibrating the meaning of both service delivery and governance legitimacy. Metrics have converged with values to create a form of institutional citizenship where any lapse in performance is seen as an ethical failure as much as a technical one. Quality has become a common language binding customers, investors and decision-makers.

Mohammad Al Gergawi, encapsulates the essence of this journey: “Those who were good stayed ahead, and the departments that weren’t good reinvented themselves; shock is the fuel that drives us toward improvement.” In many ways, the little booklet that a keen-eyed employee picked up in 1993 has evolved into a contractual framework by which public trust is measured, investment risk is gauged, and the government proves its worth every single day. Quality is no longer a ceremonial ribbon to pin on organizations, but a scale by which the strength of Dubai’s social contract is weighed granting the city its modern legitimacy as a place governed by ethical standards as much as by market logic.